Nowadays, the political climate only seems to worsen and polarize each day. Bitter, villainizing rhetoric; death threats; and politically-motivated violence is not uncommon. These appear to have escalated most recently since the end of last month when numerous bombs were mail-delivered by a Donald Trump supporter to various critics of the president, and when a man shot eleven Jewish people inside of a Pittsburgh synagogue. Some have even been comparing 2018 to 1968—another politically and socially turbulent year in U.S. history, during which: The civil rights champions Martin Luther King, Jr. and Sen. Robert F. Kennedy (Pres. John F. Kennedy’s brother) were assassinated and Chicago police battled anti-war protesters at the Democratic National Convention (resulting in 650 arrests and 300+ people injured). Some have called for a “return to civility” in political life, but can we really say that political discourse in our country has ever been “civil?” And how might we be able to guide our politics to a state of “civility?”

For starters, politically-motivated violence has been a significant part of our country’s history. Heck, this country was started by a series of politically-motivated acts of violence (the Boston Massacre, 1770; and the Boston Tea Party, 1773) and a violent war against the British. Aside from those, there has also been:

- Shays’ Rebellion (1786-87): When Revolutionary War veterans attempted armed rebellion for not having received their benefits;

- The Whiskey Rebellion (1791-94): When people staged an armed rebellion protesting the new whiskey tax;

- All of the slave rebellions (Gabriel’s Rebellion, 1800; Nat Turner’s Rebellion, 1831; plus many more);

- “Bleeding Kansas” (1854-59): When pro-slavery and anti-slavery militias fought over Kansas’ free-or-slave-state status;

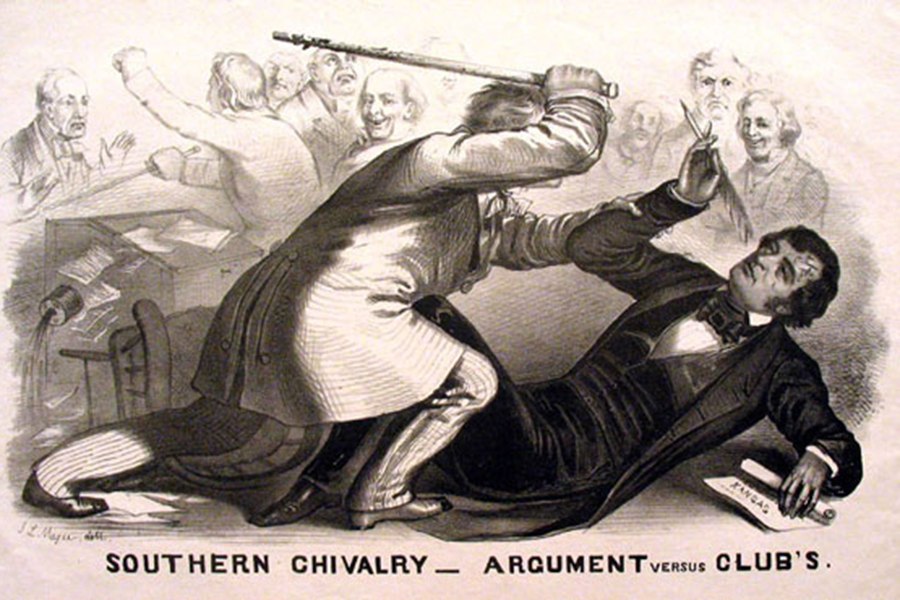

- The Caning of Charles Sumner (1856) (depicted in cover photo): When Rep. Preston Brooks caned Sen. Charles Sumner nearly to death on the Senate floor over a fiery pro-slavery speech Sumner had delivered;

- And John Brown’s raid on Harpers Ferry (1859): When the radical abolitionist led an armed raid on a federal armory to secure arms to give to slaves for a massive slave revolt.

And, of course, how can we forget the four successful (plus the numerous attempted) presidential assassinations and our very bloody civil war (1861-65) that resulted in the deaths of between 600,000 and 800,000 men? These are only the cliffnotes. Even still, these exclude the innumerable acts of politically-motivated violence since then.

Our political discourse and behavior today are certainly not “civil”; though, one can clearly discern that they are certainly more civil today than they have been at other points in our history. Just as this country began with violence, so did it too with compromise; the Constitution and the Bill of Rights were a compromise between the Federalists and the Anti-Federalists for example. It should be debated, however, to which extent compromise has ultimately been a stable or morally-correct solution. The Missouri Compromise (1820) and the Compromise of 1850 could not resolve the issues which ultimately brought about the Civil War, and the Three-Fifths Compromise resulted in black people being legally classified as “three-fifths of a person.” Despite these stains on our history, compromise is certainly better than the alternative.

Now, why has compromise been—and why is it—better than the alternative? This is because in the long-run, in the aggregate, the U.S. has become a more inclusive polity and society, and there is reason to believe we will continue along such a path into our future, thereby creating an ever-more perfect union.

There are multiple people and institutions who are responsible for the decay of our political discourse and behavior, with some holding more blame than others. However, no matter who started it or whoever is more to blame, we must compromise to bring our discourse and behavior to a more civil state. This will mean collaborating with and listening to people or a political party whom you think “[want] to destroy what you stand for” or with whom you believe “you cannot be civil.” This will mean not kicking those with whom we fundamentally disagree “when they go low.” Or “push[ing] back on them, and . . . tell[ing] them they’re not welcome anymore, anywhere.” Or not asking people to “knock the crap out of” each other. This will mean many things, but, most importantly, this will mean all of us—politicians, journalists, the media, the public, etc.—exerting collective and individual efforts to combat divisive and violent rhetoric and actions online and offline. This will be the way to civility.

-Douglas Braff