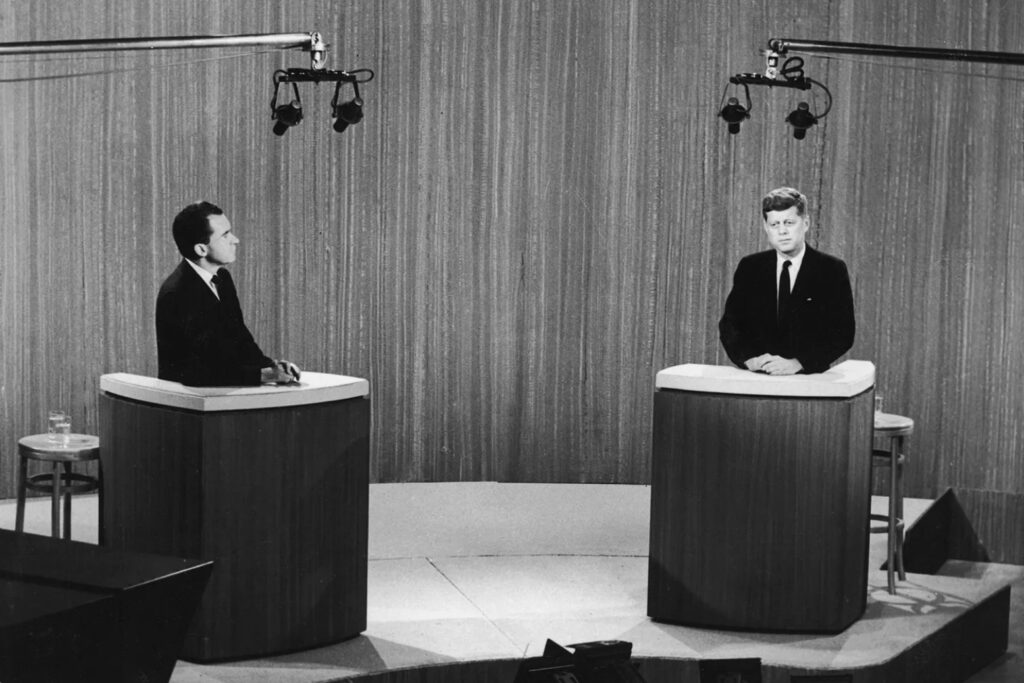

Ever since Richard Nixon sweat under the bright lights in 1960, televised debates have played a major role in each presidential election cycle. From the primary contests to the general election, candidates answer questions on a broad range of issues facing the country and engage their opponents in discourse over their respective solutions.

The presidential debates are the best chance most voters have to hear candidates speak about the problems facing the country. Increasingly, however, the debates focus less on substantive policy discussions and more on showmanship. This shift is especially pronounced in the general election debates where undecided voters are often truly engaged for the first time in an election cycle. While this criticism arguably reached its peak after the interruption-plagued first presidential debate in 2020, debates have had issues for quite some time now.

The most commonly cited issue with presidential debates is their format: instead of a free flowing exchange of ideas, these debates are repeated statements and soundbites that fit the short time allowed for each candidate. While these soundbites can be politically impactful, they can also trivialize serious issues and lower the level of discourse. For example, many argue Ronald Reagan’s 1984 debate quip where he turned the issue of his old age into an issue about his opponent’s inexperience helped him win a landslide victory that year. Reagan’s comment was perfect for the soundbite nature of the debate stage, but was arguably untrue and misleading—Mondale was 56 at the time of the debate and had served as a U.S. senator for 12 years and vice president for 4. Another example is Barack Obama’s “horses and bayonets” remark to his opponent Mitt Romney in the third 2012 presidential debate, criticizing his foreign policy as out-of-date and too Russia-centric. The remark went viral at the time on social media, but overshadowed a broader discussion on Russia that may have been relevant considering the invasion of Crimea just two years later.

Another issue is the declining importance of the debates themselves. Primary debates have been proven to affect voters’ decision making, but the impact of general election debates is less certain. Our increasingly polarized society means that there are fewer and fewer voters who are genuinely undecided as Election Day nears.

Debates with less consequence will inevitably devolve into a contest of who can appease their political base of support the most—a contest which rarely generates meaningful conversation, if ever. Their impact is as low as it has ever been according to numerous studies. Just 3% of people surveyed in one poll went into the 2020 debates undecided over who to vote for, raising questions over who will actually watch the debates in 2024 and if they should even be held. After all, if candidates are simply going to speak to their base, they might as well hold rallies on the campaign trail. Even town hall style debates, which usually occur once each cycle, do not prevent candidates from deflecting questions and transitioning to prepared remarks.

Breaking this cycle of ineffective debates begins with acknowledging their many issues and working to better them for future elections. Fact-checking debates live can be tricky, but pointed responses to blatant falsehoods can be useful for viewers, like Candy Crowley during the 2012 town hall debate with Mitt Romney. This can prevent candidates from scoring points with falsehoods (a common occurrence at many debates these days), and could also restore some trust in the media and institutions as truth-seeking sources.

Otherwise, moderators should focus on keeping candidates on-topic and from veering into statements intended solely for their bases. Letting candidates speak for longer and encouraging more articulation of the details of their policies can help lead to more substantive debates. This change involves empowering moderators to a certain extent and trusting them to cut off candidates when necessary, potentially taking the form of “sit down” style debates that have occasionally been used in the past, such as the third 2008 debate between Barack Obama and John McCain. A more civil setting, after all, can lead to a more civil discussion.

These institutional changes aside, candidates should also work to make presidential debates more relevant. A better format can help, but a joint investment in the debates as a genuine platform for discussion can save it. A commitment to a more open debate format from both parties, which resembles an actual debate rather than a joint press conference, could revive interest in the events. That is a big investment to make, considering the partisan nature of politics today, but it may be necessary to salvage one of the few remaining American traditions that actually encourages the exchange of ideas.