“I give up. I give up.”

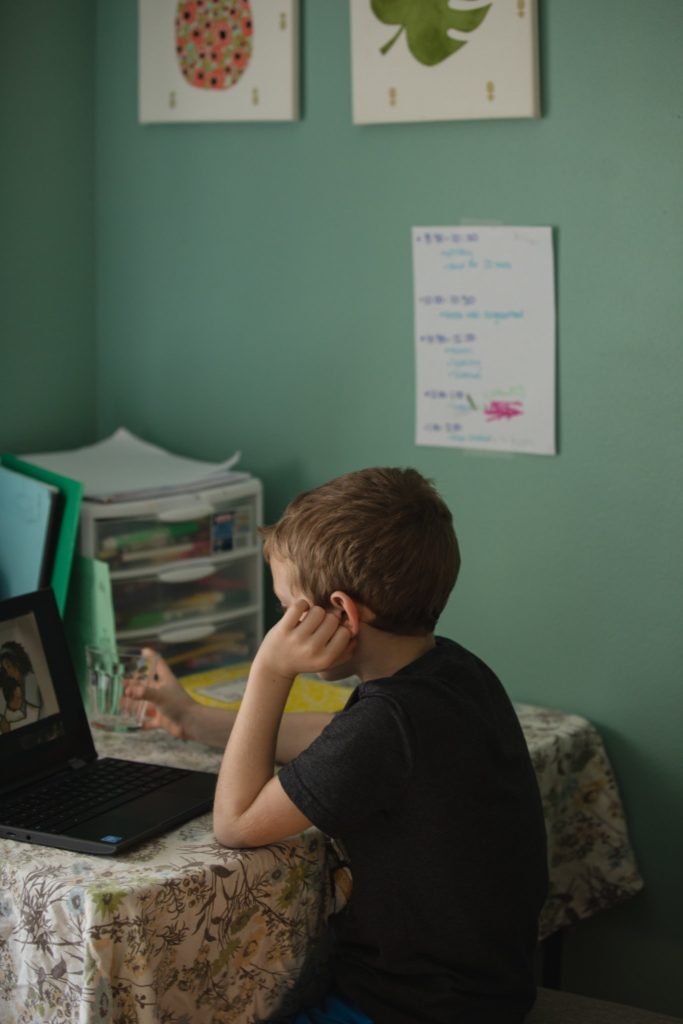

When these words left the mouth of a New York City public school elementary school teacher I work with, I laughed. Finally, the feeling that has been wracking me with guilt was being said out loud. Juggling thirty-four children, the negative effects of virtual learning can be debilitating; technical difficulties, unstable home lives, and differing learning styles plague the classroom, atop standard behavioral problems and learning disabilities. Even as only a tutor, assisting in the digital classroom four mornings a week is consistently discouraging. In the digital world, forcing a student to attend class, participate, or turn in their work becomes significantly more difficult. From family members calling students’ attention to computer games splitting students’ screens to muted televisions hidden behind screens, distractions abound. Oftentimes when called out individually, students will simply log off, logging back on just minutes later in hopes that the teacher will have moved onto someone else. In some cases, teachers have been forced to go to their students’ homes just to get them to log online.

The undeniable truth is that virtual learning is hurting students’ educational growth. American children’s test scores are down across the board in math, and in many grades in reading, as well. Anyone, including parents, teachers, and students themselves, who has first-hand experience of how kindergarten to twelfth grade students are learning right now want them back in the classroom. Still, students continue to take classes online.

Reasons as to why vary, depending on who you ask. If you ask legislators, it’s the apathy of the teachers’ unions. If you ask teachers’ unions, it’s the fear of COVID-19—an imminent threat in the absence of widespread vaccination. In New York City, nearly 200,000 elementary students returned to in-person education in November, and middle school students began their return in February. However, only roughly a quarter of the city’s more than 1 million students are back as of March—and by national standards, those numbers are impressive. In Chicago, teachers’ unions only agreed to begin returning to schools in February, and in California, legislators are just recently launching financial payouts to coax kindergarten through second grade administrators and teachers out of quarantine.With indoor dining, shopping malls, and indoor professional sports teams all open again, schools seem like the obvious next in line. After all, less than 10% percent of United States coronavirus cases have been children, and fatalities among the group are rare.

Here’s the catch: not every child is white, not every child is wealthy, and, perhaps most importantly, children are not the only citizens in the United States. Coronavirus has claimed the lives of over half a million people in the United States, and although it is slowing down, the death toll continues to rise. . Those numbers include increased risk for hispanic and Black citizens, as well as higher rates of hospitalization, and the reality that 95% of those who have lost their lives due to COVID-19 in the United States were over the age of fifty. While teachers’ unions are threatening strikes to protect themselves and their students while awaiting access to vaccines, more than half of nursing home workers refused to get vaccines when first offered. Furthermore, there is little evidence that the safety measures schools and legislators have proposed in hopes of quelling concerns about opening schools will be upheld.

People are dying. Every day, people continue to die from the symptoms of the after-effects of COVID-19. But it doesn’t quite feel like it—not the way it should, or did, at least. The photos of body bags are no longer on the front page of the newspapers, the fear of going outside has disappeared. The majority of the people left suffering are Black or the elderly. Our compassion, our pity, our guilt has faded into a brushing under the rug that allows continuous loss of life—for the citizens that we, collectively, value less.

I want my students to return to the classroom. As someone who grew up in a poverty-ridden—and, at times, abusive—home, I know how it feels for school to be your only refuge—your safe place, where everyone around you has the same resources and the fears and uncertainties of home feel far removed. Where a meal is assured, attention is given, and friendly faces are plentiful. Elementary school is a vital time and place, to not only the education but the socialization of our youth. Distance learning has only accelerated the inequalities experienced by low-income children and children of color, including increased academic and mental health obstacles. These students are more likely to have parents working in essential industries, and be directly affected by COVID-19-related deaths—and rely on schools for their mental health services. However, academic institutions still have the ability to provide these resources, and others, even with the loss of in-person learning. For children who depend upon schools for free lunches, in many districts, public schools never ceased to provide them, keeping buildings open for pick-up, and organizations across the country expanded to provide more free meals to children and families in need.

Before we allow public schools to return, we must reckon with the fact that our nation’s youth are being used as the face of a campaign intended to continue to reopen the country and ignore the deaths of entire sects of our population. Our children deserve to learn, but our citizens also deserve to live. Both of those things can be done; the only true debate is where our priorities as a nation lie.